Six steps for global sustainable food security in 2050

6 maart 2020Enough farmland to ensure a healthy diet for all people, improve global biodiversity and limit climate change in 2050

There is enough agricultural land on our planet for local and sustainable production of a healthy diet for all people now and also in 2050. The intensive global farming systems (with a lot of chemical pesticides and fertilizers) from the rich countries are therefore not needed to produce enough food to satisfy to the world population in 2050, as is often claimed. With six steps we can ensure that everyone in the world has access to sufficient and healthy food, which improves biodiversity and mitigates climate change. We make a distinction between rich countries, emerging countries and poor countries. All will have to contribute to this, but their contributions are different.

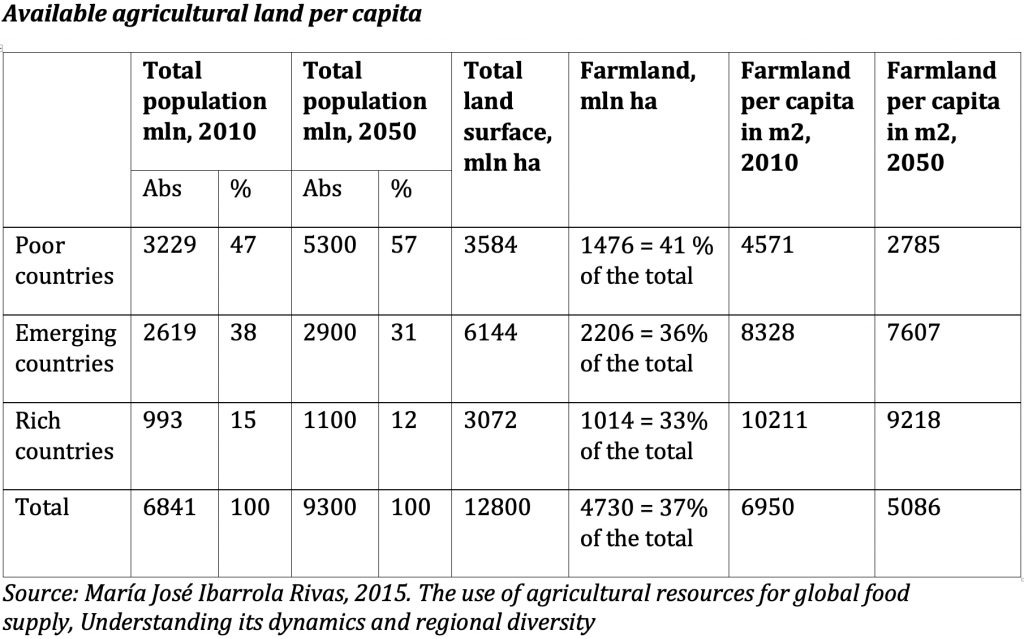

The table below shows that an area of agricultural land per capita of 6,950 m2 in 2010 and 5,086 m2 in 2050 is available worldwide. This reduction is due to the increase of the world population of 36% between 2010 and 2050.

An average US diet requires 9,600 m2 per capita. That is now achievable in the rich countries, but not in 2050 either. That is not a bad thing because meat consumption in North America is much too high for a healthy diet. If we reduce this diet to half the animal protein consumption, the land use required is still 5,280 m2 per capita. A vegetarian diet requires 4,992 m2. (World Resource Institute. Sustainable Diets: What You Need to Know in 12 Charts). By maintaining the current amount of agricultural land in 2050, more than half a hectare of agricultural land per person will be available worldwide. In principle, that is sufficient to feed all people in the world.

To provide the growing world population with sufficient and healthy food, improve global biodiversity and limit climate change, we must take the following measures: 1. Stop globally with expansion of agricultural land, 2. Eat less meat in rich countries, 3. Switch to local and organic farming globally, 4. Close production gaps between organic and regular agriculture with information and aid programs for poor countries, 5. Reduce waste and 6. Ensure fair regulated trade.

Sub 1. Stop global expansion of agricultural land

The agricultural land available per capita in the world is skewed between the poor and the rich countries. In 2010, the 15% of the world’s population in rich countries has more than double the surface area in poor countries, where almost half of the world’s population lives. And in 2050, 12% of the world’s population per capita in rich countries will have more than three times as much agricultural area as in poor countries, where then 57% of the world’s population will live.

The figures show that in poor countries there is not enough agricultural land available to produce a diet with a limited amount of meat, not even sufficient for a vegetarian diet, not in 2010 and surely not in 2050. In rich countries, on the other hand, more agricultural land is available than would be necessary for the average US diet, with a large over-consumption of meat. This crooked situation must change. This could be achieved by increasing the amount of agricultural land in poor countries, for example through further deforestation. This is not an option globally. The world’s biodiversity would decrease drastically. Moreover the carbon stored in the forests will be released as greenhouse gases (CO2 and methane) with an adverse effect on climate change. Conversely, combating climate change will have a beneficial effect on some ecosystems, such as corals, which are very vulnerable to climate change. Even if the current rate of deforestation continues – currently between 15 and 20 million ha per year – this inequality will continue to exist. In that case, the inhabitants of rich countries will still have more than 2.5 times as much agricultural area per capita in 2050 as those in poor countries. Other ways must therefore be found to balance the shortage of agricultural land in the poor countries with the surplus in the rich countries.

By not increasing the amount of agricultural land, biodiversity is maintained. Rich countries also benefit from this biodiversity, which is mainly generated in poor (and emerging) countries. They will have to provide compensation to poor countries. It is therefore necessary to achieve a trade-off between poor and rich countries: food produced in rich countries is exchanged for biodiversity generated in poor countries. The food shortage in poor countries will then be eliminated and global biodiversity will be maintained. To improve biodiversity, rich countries still have the task of organizing their own food production in a nature-friendly way. Solutions for this are conceivable in various ways; see Sub 3.

Moreover, by not expanding the agricultural land it is achieved that CO2 remains stored in the forests and therefore does not contribute to global warming. There is therefore no need to expand agricultural land, but the current available farmland should not be reduced, for example by producing biofuels for energy production. The use of agro energy and biofuels means putting the cart before the horse. Other methods, such as use of wind and solar energy, are better off for energy generation without damaging biodiversity and climate.

Sub 2. Eat less meat in rich countries

Intake of red meat in North America is about 625% of the Lancet reference diet (The Lancet, 2019: Food in the Anthropocene). This observation calls for a switch to diets with less meat in rich countries. For a healthy diet it is therefore necessary to minimize meat consumption. Because the production of meat requires much more agricultural land per calorie than the production of plants, the pressure on agricultural land and the pursuit of high production levels in rich countries therefor will decrease. As a result, opportunities exist in rich countries for more extensive production methods with more biodiversity, such as local and organic production. Moreover, in rich countries opportunities arise to supply products to poor countries for their necessary supplements for a healthy diet. See also: https://ourworldindata.org/yields-and-land-use-in-agriculture. Rich countries provide poor countries with a compensation for the biodiversity they generate, that poor countries can use to pay for the products delivered. By eating less meat, at the same time there will be less greenhouse gas emissions from cattle farming, which will limit climate change.

Sub 3. Global switch to local and organic farming

Local and organic farming can offer farmers an income and at the same time protect the fertility of the soil (e.g. through crop rotation, intercropping, polyculture, green crops, mulching, minimal tillage), close nutrient loops locally and maintain the local flora and fauna. This (and the absence of chemical pesticides and fertilizers that use a large amount of energy in their production) promotes biodiversity, environment, landscape composition, liveability of communities and human health. In addition, Halberg and others in 2006 and IFOAM Organics International in 2008 also base this on broader ethical considerations. Moreover, the disappearance of intensive farming methods reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Around 20% to 30% of global emissions come from agriculture (The Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: Food, biodiversity and climate change, 2010) and mainly from intensive agriculture in rich countries. Nitrogen (N) fertilizers are of key importance in intensive conventional agriculture. Their use is a major cause of concern with respect to environmental pollution. Most phosphorus (P) addition to watersheds is from fertiliser use in intensive agriculture. Use of chemical pesticides (containing harmful elements like cadmium) troubles pollinating insects and human health. That is why global switching to local and organic farming is needed, both for rich countries, emerging countries and poor countries.

Sub 4. Closing production gaps between organic and regular agriculture with information, extension and aid programs for poor countries

The global switch to local and organic farming will lead to a fall in production yields in the rich countries during a – rather long – transition period due to an expected yield gap. In general it takes about 10 to 15 years to turn the depleted soils back into healthy soils with an active soil life and to generate sufficient yields again. Given the relatively large amount of available agricultural land in the rich countries, this can be compensated. Moreover, less waste can make a contribution here; see Sub 5. In poor countries a production increase is possible, not by using chemical fertilizers and pesticides – which would again destroy the achieved biodiversity gains and accelerate climate change – but by narrowing the yield gap, which in the poor countries can still be considerably improved with information, extension and aid programmes.

Sub 5. Reduce waste

With regard to the food system, it is worrying that 30 to 40% of the food produced on agricultural land is wasted. Researchers like Smil and others estimated that in rich countries 15 to 20% of the food produced goes directly from the refrigerator into the waste bin. A FAO report of 2013 estimates that food waste amounts to no less than 1.3 billion tons, adds 3.3 billion tons of greenhouse gases to the planet’s atmosphere, and is good for an economic loss (excluding fish and seafood) of $ 750 billion a year.

Sub 6. Ensure fair regulated trade.

We will also have to use the relatively larger surface area of agricultural land in rich countries to make food available to poor countries. There must therefore be an export from the rich countries to the poor countries. Conversely, there will always be products that the rich countries want to consume and that only grow in the poor countries or can grow there better or more compactly, like coffee, tropical fruit, etc. On balance, more will be exported from rich countries to poor countries than vice versa. A trade deficit will therefore arise in poor countries. This can be compensated with payments from rich countries to poor countries for the conservation of biodiversity by poor countries.

To achieve these goals, regulated trade will be necessary. Liberalization and protectionism of trade in agricultural products between rich and poor countries is therefore out of the question. Currently farming in poor countries is being displaced by subsidized imports. That dumping must stop. Protectionism cmust also be condemned. It is a form of selfishness of the rich countries by refusing products from poor countries and get access to their markets. What is needed is about regulating the market in such a way that only products that poor countries need can be exported. Currently a substantial part of the imports of rich countries from developing countries consists of raw or hardly processed raw materials such as crude oil, iron ore, minerals, grains, soybeans, etc. This must stop. So no more imports of products that also grow in the rich countries are required from the poor countries, such as grains and soybeans that the rich countries use for their animal production.

At present, rich countries in three ways are disadvantaging poor countries. First, there is still ten times more money going from Africa to Europe than money going from Europe to Africa, partly due to the debt burden of Africa. Second, the rich countries have protected their own market in the past and are now pushing for free trade. As a result, the poor countries do not get the chance to build their economy. Third, the poor countries make a substantial contribution to the world’s biodiversity, while the West hardly contributes to this. It is therefore time for the rich countries to give something back to the poor countries.

Header photo: Country side in England – Credits: CPRE – Photograph in report “Food and Farming Foresight” – Paper, 2 Aug 2017

About the Author:

Dr. Harry Donkers is a scientist with experience in the fields of cost and price theory, input-output analysis, internal market, management research and philosophy. He has a PhD and is skilled in Food Technology and Econometrics. He published many research articles and various books, like ‘Local Food for Global Future’ and ‘A Better Countryside With Every Bite’. See also Linkedin.